Today I received an E-mail from Touchstone Magazine regarding today’s date in the Church year calendar. Today is Maundy Thursday. I would like to reproduce that E-mail below for your reading pleasure. Also, please refer to my wife’s post about Maundy Thursday for a brief explanation of the day.

======================

Prayer

Lord Jesus Christ, brightness of the Father’s glory and the express image of His person, who, having purged our sins, entered once into the holy place and sat down at the right hand of the majesty on high; mercifully bend our stiffened necks, we beseech You, and temper our rebellious hearts before the unspeakable mystery of Your compassion, for we ask this in Your holy name. Amen.

“Maundy,” the unusual adjective descriptive of this day, comes from the Latin mandatum, meaning “commandment,” because this is the day on which the Lord gave the “new commandment” that we are to love one another. On this day He exemplified this love by washing the disciples’ feet and also instituted the Lord’s Supper, in which all of us who share the one bread are made one body in Christ.

In many Christian bodies, following a tradition that apparently goes back to apostolic times, believers are disposed and inspired to spend at least an hour of this night, and in some cases the whole night, in prayer, remembering that Jesus Himself did so and likewise encouraged His disciples to “watch” with Him. In some monastic communities, this is a public liturgical service, and in some Roman Catholic and Anglican parishes the night is hourly divided among members to make sure that prayer is being offered in church all night long. Many other Christians keep such watch in their own homes.

March 20

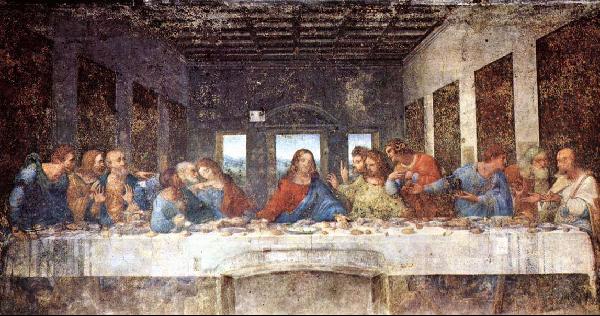

Matthew 26:17-56: We come now to Holy Thursday and the evening of the Last Supper. The traditions behind the four gospels attach several stories to the narrative of the Last Supper. These include the story of Jesus washing the feet of the disciples, a saying of Jesus relative to His coming betrayal, a prophecy of Peter’s threefold denial, various exhortations and admonitions by Jesus, and a description of the institution of the Holy Eucharist.

There are considerable differences among the four evangelists with respect to their inclusion of these components. Thus, only John describes the foot-washing, though Luke 22:24-30 includes a dominical admonition which would readily fit such a context. With respect to the actual teachings and exhortations of Jesus during the supper, John’s account is by far the longest, stretching over several chapters.

Only two of the stories are told in all four gospels. First, there is some reference by Jesus to His betrayal. In Matthew and Mark this comes before the institution of the Holy Eucharist; in Luke it comes afterwards, in John it immediately follows the foot-washing. Only in Matthew and John is Judas actually identified by Jesus. Luke and John ascribe the betrayal to the influence of Satan.

Second, all four gospels include a prophecy of Peter’s threefold denial. All of them, likewise, narrate the fulfillment of that prophecy.

The Church chiefly remembers the Last Supper, however, as the occasion of the instituting of the Holy Eucharist, and it seems a point of irony that this story does not appear in John. Perhaps he felt that this important subject had been adequately treated in the Bread of Life discourse in chapter 6.

To the three Synoptic accounts of the Holy Eucharist we must add that in 1 Corinthians 11, which is at least a decade older than the earliest of the four gospels. Indeed, this narrative recorded by St. Paul links the institution of the Eucharist explicitly to the betrayal by Judas: “I received from the Lord that which I also delivered to you: that the Lord Jesus on the night in which He was betrayed took bread . . .” This text provides clear evidence that the traditional narrative contained in the Eucharistic prayer, as it was already known to Paul when he founded the Corinthian church about A.D. 50, made mention of Judas’s betrayal. That same formula or its equivalent–“on the night He was betrayed”–is found in both the liturgies of St. Basil and St. John Chrysostom.

The Church’s testimony on this point is remarkable. It is as though some deep impulse discourages Christians from celebrating the Holy Communion without some reference to the betrayal by Judas. This reference serves to remind Christians of the terrible judgment that surrounds the Mystery of the Altar: “Therefore whoever eats this bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord. But let a man examine himself, and so let him eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For he who eats and drinks in an unworthy manner eats and drinks judgment to himself, not discerning the Lord’s body” (1 Corinthians 11:27-29).

In spite of their manifest shortcomings in discipleship, the Twelve obey Jesus, making the necessary preparations for the Seder (verses 17-19), as they had earlier prepared for His triumphal entry in Jerusalem (21:2-7). In this brief dialogue we observe that the Passover and the Unleavened Bread are fused together, as they were in practice. On the day of the Seder (Thursday of Holy Week), all leavened bread was thrown out, so that only unleavened bread would be in the house that evening. Like Mark (14:12), Matthew refers to that Thursday as “the first day of unleavened bread” (verses 17; Mark 14:1).

In this same dialogue Matthew introduces another view of the “timing” of this event. Jesus has His own “time”–kairos (verse 18). This kairos of Jesus has to do with God’s plan, though its implementation subsumes the “opportunity” (eukaria) of the Lord’s enemies (verse 16). This kairos of Matthew (missing in Mark 14:14) is identical with the “hour” in John (2:4; 7:30; 8:20; 12:23,27; 13:1; 16:21,32; 17:1). Both terms are references to God’s control of history–Divine Providence as it pertained to Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus is obviously quite conscious of this.

Whereas in Luke (22:19-23) the Lord’s mention of the betrayer comes after the Holy Eucharist, in Mark (14:19-21) and Matthew (verses 21-25), it comes first in the Supper narrative. The Lord’s knowledge of the kairos is of a piece with His knowledge of the betrayer. He is able to read both times and hearts. The scene in the Upper Room grows dramatically tense as Jesus announces what is to transpire that night.

When the Apostles question Jesus on this announcement, they address Him as “Lord”–Kyrios (verse 22). Only Judas fails to do so (verse 25). Upon His betrayer Jesus pronounces a “woe” (verse 24), prophetic of what will transpire in 27:1-10. We recall the series of seven “woes” pronounced against the scribes and Pharisees in chapter 23.

There is a particular poignancy in the setting of Judas’s betrayal: the Passover meal, the Seder. Judas has just passed from the ranks of Israel to the service of Pharaoh. Our Lord’s identification of the betrayer (verse 25), missing in Mark and Luke, is also found in John (13:26-27).

In the Greek text Judas’s question to the Lord is worded so as to expect a negative reply: “Surely not I, Rabbi?” Judas is, among other things, a hypocrite, and as such he receives a “woe” appropriate for hypocrites (cf. 23:13,14,15,23,25,27,29). Jesus’ answer to him–“You have said it”–is identical to His reply to Caiaphas (verse 64) and Pilate (27:11).

The reader knows that, while Jesus shares the Seder with His disciples, final preparations for his impending arrest are being conducted at the house of Caiaphas. The arresting party arms itself and waits the return of Judas Iscariot, who will lead them to where Jesus will be. Judas leaves the Seder early: “Having received the piece of bread, he then went out immediately. And it was night” (John 13:30).

While the plot is in progress, Jesus comes to that part of the Seder where the Berakah, the blessing of God, is prayed at the breaking of the unleavened loaf. Jesus, after praying the traditional Berakah, breaks the loaf and mysteriously identifies it as His body: “Take, eat; this is My body” (verse 26).

Because the Greek noun for “body,†soma, has no adequate equivalent in Aramaic or Hebrew, we presume that Jesus used the noun basar (sarxs in Greek), which means “flesh.†Indeed, this is the noun we find all through John’s Bread of Life discourse (6:51-56). In the traditions inherited by St. Paul and the Synoptic Gospels, the noun had been changed to “body.â€

Then, when Jesus comes to the blessing to be prayed at the drinking of the cup of wine, He further identifies the cup: ““Drink from it, all of you. For this is My blood of the covenant, which is shed for many for the remission of sins†(verses 27:28). Although Matthew uses the verb “blessed†(evlogesas) with respect to the bread, he shifts to its equivalent “gave thanks†(evcharistesas) with reference to the chalice. We find both terms used interchangeably in early Eucharistic vocabulary.

Jesus identifies the wine in the chalice as His covenant blood. It is the blood of atonement and sanctification, originally modeled in the blood of Exodus 24:8—“And Moses took the blood, sprinkled it on the people, and said, ‘This is the blood of the covenant which the Lord has made with you according to all these words’†(cf. Hebrews 13:20; 1 Peter 1:2). Matthew alone includes the words from Isaiah 53:12: “which is shed for many for the remission of sins†(verse 28; cf. the entire context in Isaiah 53:13—53:12). We recall Matthew lays great stress on the forgiveness of sins (cf. 1:21; 5:23-24; 6:12,14,15; 9:6; 18:21-35).

In biblical thought the soul, or life, is contained in the blood. Thus, those who share this chalice of the Lord’s blood participate in the very soul, the life, of Christ.

There are four verbs associated with the Lord’s action with the bread: taking, blessing, breaking, and giving. These four verbs, which are part of the narrative itself, provided the early Church with a structural outline for the Eucharistic service. This outline has been maintained to the present day. Each verb indicates a part of the Eucharistic service. To wit:

First, the “taking†of the bread became a distinct part of the service. Just past the middle of the second century, Justin Martyr wrote, “Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought†(First Apology 67). It is not surprising that this bringing of the Eucharistic elements to the table was elaborated into a procession, called the Offertory Procession in the West and the Great Entrance in the East.

Second, the “blessing†(evlogia) or “thanksgiving†(evcharistia) gave its name to the service as a whole. This long prayer always included a summary of God’s wondrous works in salvation history, coming to a climax in the recited narrative of the Lord’s Supper itself, as we see in 1 Corinthians 11. The Liturgy of St. Basil is an excellent example of this.

This long prayer, commonly called the Anaphora, came to include an invocation of the Holy Spirit over the bread and wine, an invocation born from the clear sense that only God can do what we believe to be done on the Eucharistic altar.

Third, the “breaking†of the bread, which symbolizes the Lord’s Passion, was early joined to a recitation of the Our Father, probably because of its petition to be given the “supersubstantial bread†(arton epiousion in 6:11). The loaf was traditionally broken at the end of the Our Father, and the reception of Holy Communion followed immediately. In recent times the mixing of the Holy Communion in the chalice causes a bit of a delay in this process, and some other prayers and chants have been added in the interval.

Fourth, the Holy Communion is “given.†After that, the service ends rather quickly, almost abruptly.

In these four verbs, then, the Christian Church received the outline of its Eucharistic worship.

This meal is also a foreshadowing of the eternal banquet of heaven: “But I say to you, I will not drink of this fruit of the vine from now on until that day when I drink it new with you in My Father’s kingdom†(verse 29). There is an “until†component in the Holy Eucharist, as well as a past: “For as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death till He comes†(1 Corinthians 11:26).

After the Seder, Jesus and the apostles “sang a hymn†(hymnesantes–verse 30). This final song of the Seder is the Hallel, that portion of the Psalter where each psalm begins with Hallelujah—Psalms 113-118. One of those psalms contains the line, “What shall I render to the Lord/ For all His benefits toward me?/ I will take up the cup of salvation,/ And call upon the name of the Lord†(Psalms 116:12-13). This “cup of salvation†is manifold. It is the cup of the Lord’s blood that He has just shared with the apostles, but it is also the cup of which He will soon pray, “O My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from Me†(verse 39).

As they walk eastward from the Upper Room to the Mount of Olives, Jesus continues to instruct the apostles. He tells them three things:

First, He says, in spite of all their protestations of loyalty to Him, they will very soon abandon Him in the face of danger (verse 31). Second, Simon Peter, the most vehement in his profession of loyalty, will go even further in his infidelity by denying three times that He even knows Jesus (verses 33-35). Third, when this is all over, says Jesus, I will meet you in Galilee (verse 32). This last element is the most striking of all. As in the earlier predictions of His coming Passion (16:21; 17:23; 20:19), He once again prophecies His Resurrection. He even names the place of the rendezvous! The angel of the Resurrection will later remind the Myrrhbearers of this prophecy (28:7).

The apostles will all flee this night, but even this is the fulfillment of biblical prophecy (verse 31). Once again Matthew quotes the Book of Zechariah (13:7), which is something of a textbook of the Passion in this gospel (cf. 21:5; 27:9-10).

Jesus will once again be a source of “scandal†to His disciples (skandalisthesthe–verse 31; cf. verse 33). This has been noted before (cf. 11:5; 13:52; 15:12).

We have already seen Peter’s negative reaction to the “word of the Cross†(16:21-23). In his present protestation (verse 33), he rather overdoes it, contrasting himself with the others. This story is found in all four gospels, where it serves as a warning to self-assured believers. The last word of the would-be saint is “I can handle it.â€

Jesus is content, however, to leave Peter with the last word in this discussion. Evidently there comes a time when God does not argue with us anymore. He leaves us in our pride and stupidity, not insisting on getting in the last word in His argument. God is not interested in winning arguments with us.

Then begins Matthew’s account of the Agony in the Garden (verses 36-46). Gethsemani, the very name of this place (Mark 14:22; Matthew 26:36), means “olive press,” abbreviated to simply “a garden” by John (18:1).

This garden of Jesus’ trial was, first of all, a place of sadness, the sorrow of death itself. “My soul is exceedingly sorrowful,” said He, “even unto death” (Mark 14:34; Matthew 26:38). This sorrow unto death is common to the two gardens of man’s trial.

In the garden of disobedience, the Lord spoke to Adam of his coming death, whereby he would return to the dust from which he was taken. Adam’s curse introduces man’s sadness unto death. Thus, in the Septuagint version of this story the Lord tells Eve, “I will greatly multiply your sorrows (lypas),” and “in sorrows (en lypais) you will bear your children.” And to her husband the Lord declares, “Cursed is the ground for your sake; in sorrows (en lypais) you shall eat of it all the days of your life (Genesis 3:16,17,19).

Significantly, the Gospel accounts of the Lord’s obedience in the garden emphasize His sadness more than His fear. Jesus said in the garden, “My soul is exceedingly sorrowful (perilypos), even unto death.” The context of this assertion indicates that Jesus assumed the primeval curse of our sorrow unto death, in order to reverse the disobedience of Adam. In the garden Jesus took our grief upon Himself, praying “with vehement cries and tears” (Hebrews 5:7). In the garden He bore our sadness unto death, becoming the “Man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:4).

Thus, St. Ambrose of Milan, commenting on the agony in the garden, says of Jesus: “Nowhere do I wonder more at His piety and majesty, because it would have profited me less if He had not assumed my own feelings (nisi meum suscepisset affectum). Therefore, the One that had no reason to sorrow for Himself sorrowed for me, and leaving aside the enjoyment of His eternal divinity He is afflicted with the weariness of my infirmity. He assumed my sadness (suscepit tristitiam meam), in order to confer on me His joy, and in our footsteps He descended even to the sorrow of death (ad mortis aerumnam), in order to recall us to life in His own footsteps.”

In the garden Jesus returns to the very place of Adam’s fall, taking on Himself Adam’s sorrow unto death. Thus, Ambrose regards Christ’s assumption of man’s sadness in the garden as integral to the Incarnation itself. He comments, “Therefore, I confidently use the word ‘sadness,’ because I preach the Cross, because He did not assume the appearance of the Incarnation, but its truth. Consequently, He had to take on grief (dolorem suscipere), in order to overcome sadness (tristitiam), not to exclude it. The praise of fortitude does not belong to those who bear the numbness, but rather the pain, of wounds” (Homiliae in Lucam 10.56).

The commiserating Christ bears in the garden the very sorrow incurred by fallen mankind. In this garden scene St. Cyril of Alexandria places on the lips of Jesus the following explanation of His grief: “What vinedresser, when his vineyard is desolate and laid waste, will feel no anguish for it? What shepherd would be so harsh and stern as to suffer nothing on account of his perishing flock? These are the causes of My grief. For these things am I sorrowful” (Homiliae in Lucam 146).